You may remember the beautiful National Geographic photo of a male puma, P-22, who lives in Griffith Park. His territory is very close to humans, but, as far as we know, he’s never had a problem with that. That is, until now.

It turns out that P-22 has never bothered any people, but we have unintentionally hurt him. Just 4 months after the National Geographic photo was taken, male P-22 was recaptured by biologists. This time, they noticed he didn’t look like he was doing very well – he was thin, his hair was patchy, and his skin was crusty.

April: P-22, skinny and loosing his hair, just 4 months after the previous photo was taken. He contracted mange after being exposed to rodenticide.

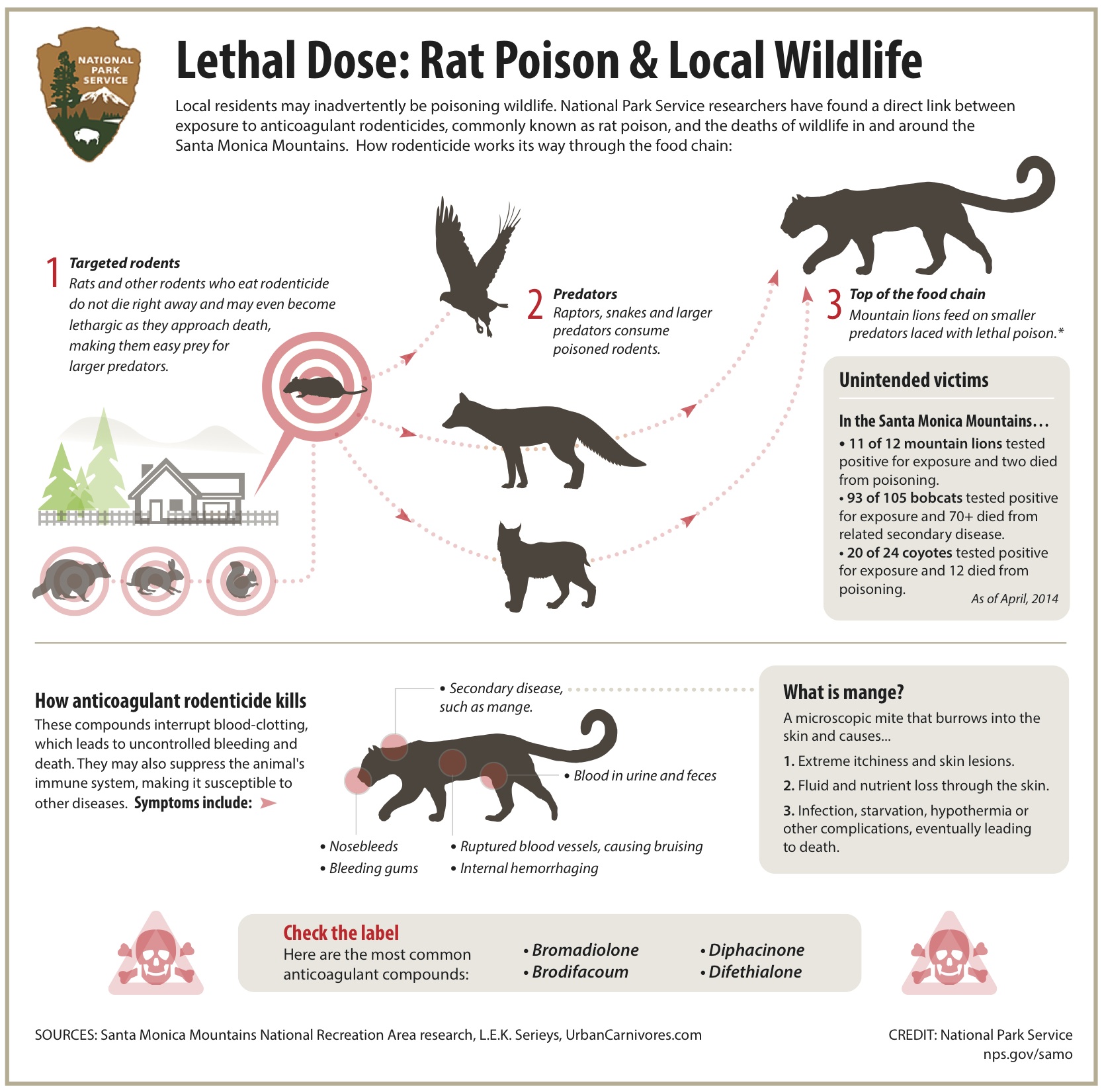

From his blood sample, they were able to tell that he had been exposed to rat poison, a potentially deadly anti-coagulant. If these poisons don’t kill a puma directly, but they can weaken their immune systems and cause secondary problems that may prove fatal. In P-22’s case, rat poison had compromised his immune system and had a severe case of mange. He was lucky this time, he was treated and released, but many other animals are not as fortunate.

P-22 is by no means the first animal biologists have found with health problems associated with exposure to rodenticides; biologists have been studying this problem in bobcats and coyotes in Southern California. We may have seen this in our study area as well.

Toxic compounds, like rat poisons, may not kill their intended rodent target right away. Rodents may ingest a small amount of rat poison, and then get eaten by a puma, bobcat, raptor, or other carnivore. Once these carnivores have eaten a few rodenticide-exposed rodents, the carnivores may accumulate a dose large enough to have toxic effects.

Luckily, starting July 1st, the state will put new restrictions in effect to limit the availability of rodenticides. However, that doesn’t mean that the rat poisons you can still buy are safe. Here are some tools to help control rodents in your home that will be safer for your family, pets, and wildlife.